Diagnostic error: Pediatric patients

ANNE M MENKE, RN, Phd, OMIC Patient Safety Manager

ANNE M MENKE, RN, Phd, OMIC Patient Safety Manager

Failure to diagnose a condition in a timely manner may lead to patient harm and professional liability exposure. From 2009 to 2013, failure to diagnose allegations accounted for 14% of all OMIC claims and over a third of all indemnity payments. The previous issue of the Digest provided an overview of the types and causes of these failure to diagnose claims. This issue will focus on diagnostic delays in the care of pediatric patients. OMIC Board Member Robert E. Wiggins, MD, and I presented this data at the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus meeting in April. Efforts to reduce the likelihood of diagnostic delay is especially critical in pediatric care since such delays can lead to death or a lifetime of bilateral blindness.

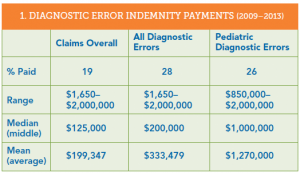

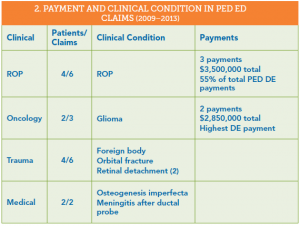

Pediatric (PED) diagnostic error (DE) claims are infrequent but costly. There were only 18 such claims involving 13 patients during the period studied, accounting for just 8% of all DE claims reported to OMIC. However, PED DE claims were responsible for 34% of the DE payments in our study and 5 of OMIC’s top 10 payments ever.  Table 1 provides comparative data on DE payments. DE claims resulted in more paid claims and a higher median and mean payment than OMIC claims overall. Payments for DE claims from pediatric patients are markedly higher than both other DE claims and OMIC claims overall. Indeed, the lowest payment in PED DE claims is $850,000 compared to $1,650 for all DE claims, and the highest PED DE payment was the most paid for any DE claim in the study. In addition, both the median and mean payments were at least $1,000,000. Information on payments for each clinical condition in PED DE claims is provided in Table 2. The three payments made to settle the ROP claims represent 55% of the total PED DE payments. The highest payment was made to settle one of the two glioma claims. OMIC did not make payments in the trauma, medical, or cornea claims, although a non-OMIC codefendant in the cornea claim settled.

Table 1 provides comparative data on DE payments. DE claims resulted in more paid claims and a higher median and mean payment than OMIC claims overall. Payments for DE claims from pediatric patients are markedly higher than both other DE claims and OMIC claims overall. Indeed, the lowest payment in PED DE claims is $850,000 compared to $1,650 for all DE claims, and the highest PED DE payment was the most paid for any DE claim in the study. In addition, both the median and mean payments were at least $1,000,000. Information on payments for each clinical condition in PED DE claims is provided in Table 2. The three payments made to settle the ROP claims represent 55% of the total PED DE payments. The highest payment was made to settle one of the two glioma claims. OMIC did not make payments in the trauma, medical, or cornea claims, although a non-OMIC codefendant in the cornea claim settled.

Standard of care evaluation of diagnostic error in PED cases.

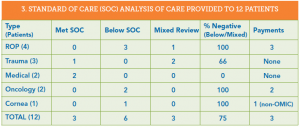

As part of the investigation of a claim, both plaintiff and defense attorneys hire experts to review the medical records and allegations in order to determine if the standard of care (SOC) was met. To help us identify areas of concern for this article, we reviewed the SOC analysis provided by defense experts (Table 3). All but one of the 13 PED DE cases were reviewed. OMIC-insured ophthalmologists were deemed to have met the SOC for only 3 patients. Care provided to the other 9 was deemed inadequate, with either below SOC or mixed reviews (classed together as negative reviews).

To further analyze what caused the diagnostic delays or errors, we looked at the role played by physicians, patients, and systems. In some cases, there were multiple factors. Physician errors stem from deficiencies in knowledge, skill, or judgment; patient factors include the patient’s condition and behavior; and system causes include the appointment scheduling process, regulations, insurance rules, and drug manufacture, ordering, and administration, etc.1,2

Physician factors predominated (73%), while system issues played a significant role. These findings are similar to those for all DE claims in our study, as we reported in the previous issue of the Digest. In those claims, physician factors impacted 71 out of 82 claims (87%), patients had no discernible impact, and system issues figured in 11 claims (13%).

Physicians were unfamiliar with clinical guidelines, showed poor judgment in when to order imaging and reexamine or refer patients, and missed key findings on exams and in photos. The lack of a differential diagnosis and absence of imaging studies together suggest that physicians are overconfident in their diagnostic ability. Time constraints or distractions during the diagnostic process may also have adversely affected the physician’s ability to correctly identify the patient’s condition. Ways used to track hospital appointments and document follow-up intervals contributed to the problems in the ROP cases, as well as deviation from well-established clinical guidelines on the timing of follow-up exams. The handoff from pediatricians and ER physicians to ophthalmologists in the trauma cases took place over the phone and did not address key aspects of the child’s care. This risky telephone care is addressed in the Hotline article. The care in the ROP and oncology claims was deemed to be below the SOC and resulted in the highest payments. The rest of the article will analyze these claims in more detail.

ROP claims

Providing care to infants who may develop ROP remains the highest liability risk for ophthalmologists. Here is an update on our claims experience, including the claims from this diagnostic error study. Since OMIC’s inception in 1987, OMIC-insured physicians and their practices have been sued for medical malpractice on behalf of 21 infants with ROP, resulting in 30 claims. ROP claims are thus low frequency events (0.6% of OMIC’s total claims). While infrequent, ROP claims are the highest severity events in our claims experience; that is, they require the most money to settle, since ROP often leads to bilateral blindness or severe visual loss. ROP claims account for 6% of paid OMIC claims. They close with an indemnity payment more than twice as often as overall claims (45% vs.19%) and have a higher mean ($932,928 vs. $199,347) and median ($487,500 vs. $125,000) payment than overall claims. Four of our top 10 indemnity payments were for ROP, including our highest ever payment of $3,375,000.

OMIC remains committed to providing assistance to those who take care of these vulnerable patients. To lessen the liability exposure for policyholders and the company overall and to reduce the occurrence of preventable blindness, OMIC developed our ROP Safety Net in 2006. It includes clinical guidelines and detailed toolkits for hospital- and office-based care. Each year, we ask policyholders if they provide ROP care and then carefully review hospital and office protocols for all who do. We also require specific ongoing education in ROP. In addition, our ROP Task Force keeps abreast of significant publications and presentations in this field and updates our policyholders accordingly. Recently, for example, our ROP Task Force reviewed new studies of the effect of anti-VEGF agents on the infant’s neurodevelopment. We revised our consent form, recommendations, and conditions of coverage to address these concerns. See the Policy Issues article in this Digest for more details. For a detailed analysis of the many causes of this diagnostic delay, see “Retinopathy of Prematurity: Create a Safety Net” available at omic.com/rop-safety-net/.

Oncology claims

Pediatric patients whose cancer diagnosis was allegedly delayed make very sympathetic plaintiffs in a medical malpractice lawsuit. Both cases of diagnostic error in our study involved glioma. A review of the expert opinions in these two claims provides guidance on how to prevent this diagnostic error.

The first case involved a pediatric ophthalmologist who had diagnosed this condition before. The patient, however, had none of the signs and symptoms he associated with glioma and at 9 months of age was younger than usual for its presentation. The pediatric ophthalmologist’s familiarity with the condition and clear sense of how the condition usually presented gave him confidence when appraising the child. He attributed the child’s asymmetric nystagmus to spasmus nutans (SN) and reassured the parents, asking them to bring the child back at age 2 or earlier if strabismus developed. In his letter to the child’s pediatrician, the ophthalmologist was also reassuring: he stated that a different kind of nystagmus in older children was associated with tumors, but he wasn’t worried about a tumor in this younger child. Unfortunately, his diagnostic certainty was not warranted. When examined again at age 4 (two years later than advised), the child’s condition had significantly deteriorated and an MRI was ordered, which detected the glioma. The child ultimately lost all vision.

The plaintiff expert insisted that imaging studies were required as of the first visit with a finding of asymmetric nystagmus, and that follow-up should have occurred in three to six months. The defense expert clarified that imaging was not standard at the time of care. The defense expert was concerned, however, that the ophthalmologist made SN his definitive diagnosis in the letter to the pediatrician without doing anything to confirm it. He also agreed with the plaintiff experts that follow-up was needed much earlier, citing literature from the time that urged close follow-up. The case settled with the defendant’s permission for $2,000,000.

While the ophthalmologist in the first case believed he knew the cause of the child’s condition, the defendant in the second glioma case never arrived at an explanation for the child’s vision loss. The 9-year-old child had been referred by an optometrist after vision in the right eye had deteriorated from 20/50 to 20/200 over the course of three years despite vision therapy. On initial exam, the ophthalmologist noted a pale optic nerve and hypoplasia. He continued the vision therapy and requested a return visit in nine months. The parents did not feel the vision therapy was helping and returned one month later. Despite the parents’ concern and a decrease in visual acuity to 20/400, the ophthalmologist described the condition as “stable.” It was only when vision had deteriorated to HM on the right and 20/400 on the left that the ophthalmologist referred the patient to a neuro-ophthalmologist, who ordered the MRI that detected an optic nerve glioma.

Plaintiff and defense experts criticized the defendant for failing to appreciate and discern the cause of the deteriorating vision. They also noted the differences in his exams and those of the neuro-ophthalmologist, who found an afferent pupillary defect not mentioned by the defendant and described only optic disc pallor rather than optic nerve hypoplasia. All experts felt that poor vision and a pale optic nerve in a child required an immediate referral to a neuro-ophthalmologist. This case settled with the defendant’s permission for $850,000.

Slow down the diagnostic process

Ophthalmologists know that infants being screened for ROP are high risk. These two glioma claims show that extreme caution is also required when pediatric patients present with neurological symptoms such as acquired nystagmus and unexplained vision loss accompanied by optic disc pallor. Ophthalmologists should be wary of atypical presentations and consider early referral to a neuro-ophthalmologist. If they choose to monitor the patient themselves, diagnostic studies and close follow-up are needed to confirm the diagnosis and rule out vision- and life-threatening tumors.

Join OMIC’s Chairman Dr. George Williams in asking yourself “How sure am I of the diagnosis?” Here are some more ways to help make the diagnostic process more deliberative. “Can I explain what is wrong to the patient?” Tell patients when you are not sure of the cause of the loss. Explore alternative diagnoses by asking “Could this be something else?” and rule out the worst case scenario by asking “If I am wrong, what don’t I want this to be?” Watch for unexplained findings and test results that challenge your diagnosis. Review prior records to check for long-term changes that signal worsening of the condition, such as vision that deteriorates slowly.

1. Gandhi TK et al.”Missed and delayed diagnoses in the ambulatory setting: A study of closed malpractice claims.” Ann Intern Med. 2006; 145: 488-496. 2. Hoffman J, ed. “2014 Benchmarking Report: Malpractice risk in the diagnostic process.” Crico Strategies.

Spotlight: Byron H Demorest MD, Father of OMIC’s Risk Management Program

Byron H. Demorest MD

Byron H. Demorest, MD (1925-2011) was a giant in the field of ophthalmology. He was widely considered, along with Jerome Bettman, MD to be on the forefront of modern day ophthalmic ethics. A member of the original OMIC steering committee, Dr. Demorest was a founder of our company and was OMIC’s first Risk Management Committee Chair. He was on OMIC’s first Board of Directors and served until 1996.

First OMIC Board of Directors

During his tenure, Dr. Demorest co-authored the OMIC-published book Practice Without Malpractice in Ophthalmology. The book was the first comprehensive look at ophthalmic professional liability and loss prevention from the physician’s point of view. Dr. Demorest and Dr. Bettman drew from years of experience working on behalf of the American Academy of Ophthalmology to improve patient safety and protect eye care providers from malpractice lawsuits.

In addition to authoring books and articles for OMIC, Dr. Demorest oversaw the introduction of The OMIC Digest, our newsletter which recently celebrated its 100th edition. He also presided over the creation of OMIC’s popular seminar series, which have been presented at venues across the country over 1,000 times, and the OMIC Hotline which has assisted insureds more than 20,000 times since its debut in 1993.

Dr Demorest at first OMIC Board Meetings

Dr. Demorest was born on May 1, 1925 and died October 14, 2011. Byron was married to Phyllis on September 2, 1947, and they had two daughters, Katheryn and Susan, and one son, John. Byron’s undergraduate education was obtained at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln. It was completed at Omaha University (now of University of Nebraska in Omaha). He obtained his BS degree in 1947 and his medical degree in 1948. His internship was obtained in Charles T. Miller hospital in St. Paul, MN. His residency in ophthalmology was at Washington University in St. Louis, MO from 1951 to 1954. He was an assistant clinical instructor in Ophthalmology at Stanford University from 1955 to 1960. Byron was the founding chairman of the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of California, Davis. He was certified by the American Board of Ophthalmology and subsequently was an Associate Examiner for the Board until 1965. Byron was a member of the American Academy of Ophthalmology and he served as its president in 1985. Other memberships included The Pacific Coast Ophthalmological Society, the California Association of Ophthalmology, the American Association of Ophthalmology. He also served as president of these organizations. Byron also had active duty with the navy, ending up as a Lieutenant Commander and Chairman of the Eye Department at the Great Lakes Naval Hospital.His Sacramento involvement included being the 1975 president of the Golden Empire Council, BSA, Elder of Fremont Presbyterian Church, Chairman of Sacramento Symphony Association in 1968, moderator of a daily television program, called ‘Doctor’s Notebook’ on KCRA Channel 3 from 1970 to 1973.

Rob Fante, MD – OMIC Nominee to Academy’s Leadership Development Program (LDP) XIX Class of 2017

OMIC Risk Management and Underwriting Committee Member Robert G Fante, MD, FACS, of Denver Colorado was accepted for the LDP XIX, Class of 2017. Dr. Fante was nominated by OMIC to join a select group of twenty participants chosen from among a large group nominated by state, subspecialty and specialized interest societies.

OMIC Risk Management and Underwriting Committee Member Robert G Fante, MD, FACS, of Denver Colorado was accepted for the LDP XIX, Class of 2017. Dr. Fante was nominated by OMIC to join a select group of twenty participants chosen from among a large group nominated by state, subspecialty and specialized interest societies.

The purpose of the Leadership Development Program (LDP) is to provide both orientation and skill development to future leaders of state, subspecialty and specialized interest societies. Nominees to the LDP must agree to develop a project that will benefit the nominating group.

The subject of Dr. Fante’s project will be lessons learned from closed oculofacial plastic surgery cases over OMIC’s 30 year history, with particular focus on trends in the past 10 years. The types of claims and complaints that arise for the oculoplastic subspecialty are somewhat different than those for other branches of ophthalmology, and the levels of indemnity are often higher. As the largest single carrier for this subspecialty, OMIC is in a unique position to have useful data that will hopefully reveal trends that can then be used to mitigate claims and improve patient safety.

This project will analyze details and statistics on the types of oculoplastic claims that OMIC has experienced with review of a few cases to illustrate particular points related to cosmetic surgery, informed consent, standard of care violations, etc. The oculofacial plastic surgery claims data has not been previously studied at this level of detail, and is quite interesting. Dr. Fante will also review physician strategies that are associated with getting into malpractice trouble, and those that are associated with staying out of trouble, as well as suggested algorithms to mitigate difficult situations.

More about Dr. Fante at https://www.drfante.com/

Play Ball!

GEORGE A. WILLIAMS, MD, OMIC Board of Directors

As a lifelong Chicago Cubs fan, I understand the topic of errors better than most folks. Sometimes errors are the individual’s fault. Sometimes, they are the team’s fault. I can’t count the number of times I’ve seen a routine pop fly drop among three Cubs players in a classic example of “I got it. You

take it.” Similarly, errors in medicine can be the fault of the individual or the fault of the team. The difference is that unlike in baseball, medical errors truly matter.

This issue of the Digest summarizes OMIC’s experience with diagnostic errors in pediatric patients. My thanks to Anne Menke and Bob Wiggins for providing these excellent examples of OMIC’s continuing quest to improve care.

It is a sobering report at multiple levels. First and foremost, it is a story of lost opportunity to prevent visual loss or even death in a child—an always tragic occurrence. Second, it demonstrates the personal consequences to the involved ophthalmologists, who are often devastated by the realization that their care has been judged to be negligent. Finally, and frankly least importantly, we see the substantial financial ramifications of such errors.

When I say the financial costs are the least important part of the story, it is not because the money does not matter. It does. Your Board carefully considers our fiduciary responsibility to our insureds on every settlement. Fortunately, OMIC has the financial strength to provide appropriate and fair compensation when patients have been harmed due to negligence. The most important issue is to understand what went wrong.

Each of these cases presents an opportunity to ask two important questions: How did this happen and what can be done to prevent it from happening again? Sometimes, it is simple physician error. We all make mistakes and in the current era of increasing patient volumes, increasing clinical knowledge to be mastered, and the often maddening regulatory and documentation requirements, I don’t see practice getting any easier. That makes it all the more important that we take the time to ask ourselves how sure we are of a diagnosis and to think what else could this be, particularly when managing an atypical presentation or clinical course. If we are not certain, close follow-up and a second opinion demonstrate to the patient our concern.

As noted by Bob and Anne, sometimes the answer is a systems-based failure. Medicine is transitioning to a future of team-based care in which systems of care will become increasingly critical. Nowhere in ophthalmology is this more apparent than in the management of ROP.

Several years ago, OMIC’s claim experience in retinopathy of prematurity demonstrated the need to approach ROP from a systems-based perspective. As a result, OMIC developed an evidence-based underwriting process that establishes a rigorous educational program involving not only ophthalmologists, but their offices and neonatal intensive care units as well. We call this process our “Safety Net” and if we can catch even one child, everyone wins. The Safety Net is a dynamic, evolving process and OMIC provides it free to everyone whether an OMIC insured or not. Under the direction of pediatric ophthalmologist Robert S. Gold, the OMIC ROP Task Force is continually evaluating

the Safety Net to reflect the best available evidence for the diagnosis and management of ROP. It is another example of the synergy between good medicine and good business.

I am told that this year is different for the Cubs. I hope so. One thing that will not be different is your company’s continuing dedication to patient safety. Baseball players often shrug off their errors with the attitude that they will get the next one. For our patients, there is no next one. I got it, you

take it is no way to play ball or practice medicine.

take it is no way to play ball or practice medicine.