Medicolegal Implications of Using Off-Label Drugs and Devices

By E. Randy Craven, MD, and Elizabeth C. Moran, JD

Digest, Winter, 1996

Most physicians have heard these words: “Doctor, isn’t there anything else you can do? Some new treatment you can try?” Patients often perceive “new” treatments as better or less problematic than existing treatments and pleas for something “new” are particularly understandable when patients are faced with a terminal condition or loss of vision. Physicians generally look for proven treatments that will give their patients the best results with the least side effects. However, because of the tremendous psychological leverage of offering something “new,” physicians might be tempted to try unproven treatments to keep up with market forces. A good example of how market forces lead to such decisions might go something like this: “Mrs. Jones, you have the privilege of being in the right place at the right time. I am excited to inform you that I use the latest technology. The old method of correcting myopia is out and my new technique is in. In fact, because of my commitment to stay on the cutting edge, the laser I will be using to reshape your cornea was designed by me with the help of an engineer. This laser will correct your myopia in minutes.”

What assurance does Mrs. Jones have that the laser developed by her ophthalmologist is safe? Is it prudent for physicians to develop their own equipment or drugs for use on their patients? Who or what regulates physicians who do so?

Regulation of Physicians’ Practices

Production, sale, and clinical research of new drugs and medical devices are subject to regulation by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Physicians and patients are protected to some degree when they use drugs or devices that have undergone the scrutiny of the FDA and received approval for marketing and sale. The known indications, hazards, and adverse effects of the approved device or drug are required to be included in the product labeling. The FDA can restrict the ability of a company to sell, manufacture, or import a drug or device and can impose a variety of other protective measures.

Ordinarily, physicians are not directly regulated in their use of drugs and devices in day-to-day practice but are expected to practice in a manner that is designed solely to insure the well-being of the patient. Unless a physician is himself marketing or selling a drug or device, or acting as an investigator in clinical research, the FDA generally does not oversee or interfere with a physician’s individual practice decisions.

It is a different matter when the physician is conducting clinical research. Research activity occurs when the clinician conducts a “systematic investigation” designed to develop or contribute to “generalizable knowledge” such as by testing a hypothesis, drawing conclusions, and developing a base of knowledge from the results, especially concerning safety or effectiveness of the product.

If a practicing physician departs from usual (standard) treatments for an individual patient, such as by using a self-made device, a modified device, or a marketed drug for an off-label use, such use does not in and of itself constitute “research.” However, the non-standard treatment might constitute a deviation from accepted standards of medical care. The standard of medical care, which is based upon what reasonable physicians in the same specialty would do at the same time under similar circumstances, is overseen by state and local medical boards, and indirectly, by malpractice lawsuits. Issues of deviation from standards of care are usually raised by patients and/or other practitioners filing a complaint with their state or local medical board or by patients bringing malpractice lawsuits. The medical board also may be informed of aberrant practice styles by federal agencies, such as the Health Care Financing Administration and Medicare Peer Review Organizations.

In addition, local hospitals and clinics oversee standards of medical practice through credentialing, peer review, and quality assurance procedures, which involve investigations of standards of care, identification of deficiencies, and establishment of minimum qualifications for privileges. This is why malpractice insurance companies request information relating to licensing sanctions, peer review proceedings, and denial or surrender of hospital privileges.

So Mrs. Jones is protected by community standards, state and local agencies and institutions, and to a lesser degree, by agencies of the federal government.

Physician Practice versus Investigational Use

A physician may manufacture his or her own equipment or devices solely for his own use in his practice, and may use approved products for non-approved (off-label) applications. In fact, off-label use of medication is quite common. Distinguishing off-label use of drugs or devices as part of a physician’s practice from “experimental” or “investigational” use may be difficult at times. If the new use is based on firm scientific rationale and sound medical evidence, and is not for the purpose of developing information about safety or efficacy (for example, to support a request for FDA approval of the new use or to support advertising of new uses for the product), the use generally will qualify as “the practice of medicine” rather than “investigational use.”

However, if the physician is gathering new information on multiple patients, particularly for publication purposes or to obtain approval for a new device or new use, it is probably considered research, and the physician must comply with the panoply of federal statutes and regulations governing all aspects of approval of new drugs and devices, including numerous requirements for the protection of human subjects in research. In most cases, the practitioner will be required to obtain approval from his or her local Institutional Review Board (IRB), a committee that operates under HHS and FDA regulations for the purpose of protecting the rights of research subjects. The FDA will not accept research data in support of a new drug or device application unless the research protocol and consent documents have been reviewed and approved by an IRB. Similarly, peer reviewed journals usually require documentation of IRB approval before research results will be accepted for publication.

The FDA does have the right to request tracking of marketed products and, although off-label uses in medical practice are not generally regulated, the FDA can disapprove an existing product, require additional warnings, and/or request a recall of a product if it is not happy with off-label uses of the product. Otherwise, regulation of a physician’s medical practice generally falls under the jurisdiction of the state and local agencies previously discussed.

Liability and Insurance Issues

If a physician develops a new device, such as a new ultrasound for phacoemulsification to use on patients in the office, he or she may well face additional liability exposure for problems resulting from the use of the device. Injuries caused by the use of non-approved devices and drugs generally fall within the scope of malpractice and general liability coverage, but a physician may be exposed to personal risk as well if the insurance policy does not cover the liability associated with such uses.

For this reason, it is a good idea to contact your professional liability carrier about potential liability exposure if any of your practice activities involve the use of a self-made instrument or off-label use of drugs or devices regardless of whether they have gone through IRB approval. OMIC, for example, has carefully considered the use of the excimer laser in photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) and laser assisted in-situ keratomileusis (LASIK) and has developed internal guidelines intended to help reduce the increased professional liability and exposure to claims associated with their use.

Off-label applications of drugs also increase the potential for liability, although many drugs are widely used this way. A good example is mitomycin-C (Mutamycin) for glaucoma surgery. Mitomycin-C is FDA approved “for the use of disseminated adenocarcinoma in conjunction with other approved chemotherapeutic agents.” There is no mention of using this drug for pterygia or glaucoma surgery, and there is a long list of side effects for this drug, including pulmonary toxicity that does not appear to be dose related. Nevertheless, glaucoma surgeons are using this medication with increasing frequency, and even a few general ophthalmologists are using it to prevent the recurrence of pterygia following excision.

OMIC has considered the use of mitomycin-C and other off-label drugs (such as cyclosporin drops) and has this general recommendation:

When using a new or old drug in an approved manner, proceed with a green light. If it is an existing drug used in a non-approved manner (off-label), first consider whether its use poses significantly increased risks to the patient. Second, consider whether its use can be expected to bring good results without a higher complication rate. If it presents no more risk to the patient than that of daily living, proceed with its use; for example, the use of aspirin for anticoagulation after a central retinal vein occlusion. If there is an increased risk to the patient, ask yourself if at least a reasonable number of physicians in your specialty are using the treatment; that is, have peer reviewed articles been published supporting the use of the new treatment and is the treatment being used by a reasonable number of other practitioners with the same level of training as you?

Ophthalmologists are considered medical “specialists” and in most cases are held to a “national” rather than “local” standard of care. The same is true of subspecialists in various areas of ophthalmology. An ophthalmologist may face increased liability for off-label uses if a reasonable number of similar specialists or subspecialists are not using the same new treatment. An ophthalmologist whose patients experience more problems with off-label use of a medication than they would with standard methods of treatment might well be subject to professional criticism, and thus be exposed to malpractice liability and potential licensure or credentialing actions.

Additional Precautions

When considering new techniques, new devices, or new uses for approved drugs, practitioners need to think about taking additional measures to protect themselves as well as their patients. If you select a treatment for an individual patient with the intent that it will enhance the patient’s well-being, and there is sound medical evidence supporting the treatment, you are likely to be on solid ground. In such cases, FDA regulation is generally not controlling, and you probably will not need IRB approval unless the treatment so departs from standard practices that it may be considered experimental or investigational, or it presents significantly increased risks for the patient, and/or you wish to use the information for study purposes.

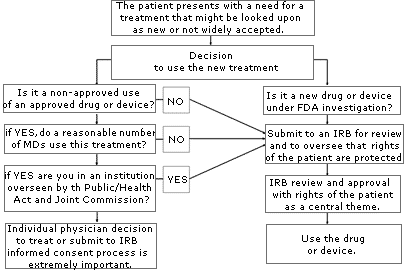

If you are uncertain about whether your use of a treatment or device might be considered “investigational” or “experimental,” consult your local IRB. An IRB is usually available at your local institution (some regional IRBs also exist) to review your proposed use and determine if it constitutes “research” requiring IRB approval. Similarly, if you are unsure whether the treatment has sufficient peer support or is simply too new, or if the literature is unclear, consider going through an IRB to help you with your decision. The flow diagram set forth on page A-78 may help you through the process of determining if you should submit your treatment proposal for IRB review.

Anytime you are considering unapproved uses of a device or drug, the informed consent process and its documentation, including treatment alternatives, should be thorough and specific in case you are later called upon to defend your decision to use non-standard treatments. If you have a specific area of concern, contact OMIC’s Risk Management Department for further information or referral to the appropriate resource or agency.

Advertising for Medical Services

Anne M. Menke, RN, PhD, OMIC Risk Manager

Digest, Summer/Fall 2004

Allegations related to physician advertising are surfacing with increasing regularity in medical malpractice claims. In addition to alleging lack of informed consent, patients are using state consumer protection laws to claim that the physician defrauded them. This exposes the physician to punitive damages and other uninsured risks.

Physician advertising is regulated by state law as well as by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) under provisions of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act (FTCA). The American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) and the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery (ASCRS) have issued guidelines to advise their members on relevant ethical and professional standards.

Advertising “includes any oral or written communication to the public made by or on behalf of an ophthalmologist that is intended to directly or indirectly request or encourage the use of the ophthalmologist’s professional medical services … for reimbursement” (ASCRS Guidelines). These guidelines therefore apply to print, radio, and television advertisements as well as to informational brochures, seminars, videos, and the Internet.

The FTCA prohibits deceptive or unfair practices related to commerce and “prohibits the dissemination of any false advertisement to induce the purchase of any food, drug, or device.” The FTCA and the professional guidelines state unequivocally that advertising for medical and surgical services must be truthful and accurate. It cannot be deceptive or misleading because of (1) a failure to disclose materials facts, or (2) an inability to substantiate claims – for efficacy, safety, permanence, predictability, success, or lack of pain – made explicitly or implicitly by the advertisement. It must balance the promotion of the benefits with a disclosure of the risks and be consistent with material included in the informed consent discussion and documents.

Lack of Informed Consent Allegations

When not carefully crafted, advertising runs the risk of overstating the possible benefits of a procedure and potentially misleading patients into agreeing to undergo surgery without fully understanding or appreciating the consequences and alternatives.

In a sense, an advertisement becomes a ghost-like appendage to boiler-plate informed consent forms. If an advertisement overstates the benefits, misrepresents any facts, or conflicts with other consent documentation or patient education material, it can potentially make a jury believe the physician may have overstepped the line of ethical propriety by creating unrealistic patient expectations. Legally, such a scenario might allow a jury to conclude the patient was not given a full and fair disclosure of the information needed to make a truly informed decision.

Punitive Damages and Other Uninsured Risks

Another pitfall for the ophthalmologist who markets medical services are state laws that may allow the plaintiff to ask for punitive damages, which could double or treble the amount of money awarded to the patient by the jury. Physicians should be particularly concerned about such allegations since most professional liability insurance policies, including OMIC’s, do not pay for such damages.

OMIC’s underwriting guidelines state that advertisements and marketing materials must not be misleading, false, or deceptive and must not make statements that guarantee results or cause unrealistic expectations. In addition, insureds are required to abide by FDA- and FTC-mandated guidelines and state law. OMIC has specific policy language limiting its professional liability coverage to defense costs for claims related to misleading advertisements. No payment of indemnity will be made.

Therefore, if a plaintiff is alleging medical malpractice and has an added allegation of fraud, your OMIC policy will provide defense for both the allegation of malpractice and fraud but would limit any indemnity payment to awards related to the medical malpractice allegation of the lawsuit.

2021: Updated advertising medical services

Employee-Related Suits on the Rise

By Kimberly Wittchow, JD

OMIC Insurance and Group Products Associates

[Digest, Fall 1998]

In the litigious business environment of the 1990s, ophthalmic practices of all sizes are increasingly vulnerable to employment practices liability suits. Small and large practices alike are discovering that discrimination, sexual harassment and wrongful termination suits can wreck havoc on their bottom line, as even frivolous or unsubstantiated claims must be defended, often at considerable expense to the practice.

The media is replete with stories of employers being sued even those who insist they “did everything right.” Take, for instance, the female employee who resigned and sued her former employer for sexual harassment in part because one of the company’s owners gave her a scarf on Valentine’s Day. The company claimed it investigated the situation after the employee complained and acted to protect her from further incidents. Nevertheless, a federal court jury awarded the plaintiff $82,000, which the company had to pay, along with its own substantial legal defense costs.

A case in the South arose when an accounting clerk in a medical office threatened to sue, stating that she was having sex with one of the directors. Previously a virgin, the woman claimed that on some occasions sex was consensual, but at other times she was forced to participate. Rather than face a Bible Belt jury, the practice opted to settle for over $35,000.

At one company, three former employees sued, alleging they were fired as a result of age discrimination. The three employees were able to prove that the rating system used by their employer to determine which employees to keep and which to terminate treated older employees unfairly. They won their case and were awarded $8.8 million in damages.

One young female doctor sued when she was not offered partnership after five years at a medical practice. Although she alleged that she had been discriminated against because of her gender and her pregnancy, the senior doctors claimed she was not offered partnership because her work was subpar. When new, potentially incriminating evidence came to light, the partnership settled for $22,500 and paid $5,000 in legal fees.

To make matters worse, damages in an employee suit for sexual harassment often do not end up with the employee’s claim against the offending co-worker. A recent trend has been a rapid rise in the number of counter complaints brought by the offending co-worker against the company for wrongful termination, demotion, defamation and breach of contract as a result of the harassment charges. These claims by supervisory level employees can be more expensive to defend and resolve than the underlying harassment suit.

Who Needs EPLI Coverage?

No ophthalmic practice is immune to lawsuits. Any practice with employees should seriously consider adding Employment Practices Liability Insurance (EPLI) coverage.

EPLI policies typically provide coverage for the health care entity; current and former appointed directors, trustees and officers; and current and former employees, including supervisory and managerial employees. Many carriers offer endorsements that allow other types of employees to be added to the policy. For instance, under the EPLI policy developed by OMIC and the American Academy of Ophthalmology, endorsements can be added to expand the definition of covered insured to include leased employees, independent contractors and leasing companies.

What Does EPLI Cover?

EPLI generally covers wrongful employment practices directed against any employee, former employee or employment applicant arising out of an employment relationship. OMIC offers an endorsement for third party coverage that includes claims brought by non-employees for sexual harassment or discrimination in the workplace. Wrongful employment practices covered by OMIC include:

- Discrimination on the basis of race, religion, age, sex, national origin, disability or any other protected class established pursuant to federal, state or local law.

- Harassment, sexual or other.

- Wrongful termination, including wrongful discipline or evaluation; retaliation; demotion; failure to hire or promote; or breach of employment contract.

In considering which EPLI policy to buy, it is important to evaluate additional coverage features. For example, OMIC’s ELPI policy automatically includes coverage for prior acts. This means that coverage is provided for claims made during the policy period arising from incidents unknown to the company that occurred before the policy effective date. If a practice does not require prior acts coverage, OMIC can exclude it from the policy and discount the premium accordingly. Another important feature of OMIC’s EPLI policy is a duty to defend clause. This requires the carrier to defend against all covered claims regardless of their legitimacy. OMIC includes the duty to defend as a standard coverage feature.

Your EPLI carrier should allow you to select from a broad range of coverage limits. For example, OMIC policy limits range from $50,000 to $2 million per claim and in the aggregate, including defense expenses. Various deductibles are available starting at $5,000.

Risk Management in the Workplace

Two recent U.S. Supreme Court rulings (Ellerth V. Burlington Industries, 118 S. Ct. 2257 [1998] and Faragher v. City of Boca Raton, 118 s. Ct. 2275 [1998]) reminded employers that they can defend themselves against sexual harassment claims when there are adequate and workable procedures in place that invite employees to complain and allow the employer to take appropriate action against the offender.

OMIC, likewise, realizes that prevention is the key to both a discrimination-and-harassment-free work environment and to cost containment in the employment practices litigation arena. In December, OMIC conducted its first nationwide risk management audioconference on employment practices liability. A one hour EPLI program was held at the OMIC booth in New Orleans in conjunction with the Academy’s annual meeting. Additional EPLI-related programs will be held in 1999.

For information on OMIC’s program, please contact the Underwriting Department at (800) 562-6642, extension 639.

Notify OMIC of Changes in Your Practice

By Kimberly Wittchow, JD OMIC Staff Attorney

Digest, Spring 2005

It is important to OMIC that our insureds remain adequately protected from liability, especially during times of change and transition. By accepting your OMIC policy, you agree that the statements you made in the application are true. Most insureds supply accurate and thorough information both on the written application and in follow-up correspondence with their underwriter. However, after the underwriting process is complete and the insured is accepted for professional liability coverage, insurance may not be at the forefront of his or her mind. Nevertheless, it is important that insureds continue to communicate with their underwriter about any changes that occur in their practice.

Change in Practice Activities, Arrangements and Locations

The policy requires that insureds promptly inform OMIC, in writing, of any changes to the representations they made in their application. And insureds warrant, when signing the application, that they will update the information supplied on the application as necessary. This ensures that the coverage you have and the premium you pay correspond to your risk exposures.

• For instance, if you begin to perform a new refractive surgery procedure, you must complete and submit a supplemental questionnaire for this procedure. If OMIC grants your coverage request, your policy, which excludes coverage for all refractive surgery procedures, will be endorsed to provide coverage for the particular approved procedure.

• If you hire an optometrist or certified registered nurse anesthetist or bring in a locum tenens, you will want to ensure that he or she has his or her own insurance, or else is accepted for coverage by OMIC under your policy.

• You must alert OMIC when your practice arrangement changes, for example, if you join another practice, form a partnership with others, incorporate your practice, or allow outside utilizers to use your surgery facilities. You and your underwriter can discuss what options you have for deleting, adding, or otherwise changing your entity coverage and what limits are available or required for you to maintain.

• You must notify your underwriter if you significantly reduce your hours, eliminate certain surgical activities, or discontinue surgery altogether, so that your coverage can be amended and premium discounts, if any, can be applied.

• You must notify OMIC if you move or begin to practice in additional counties or states because your premium may need to be adjusted.

Claims, Complaints and Medical Conditions

While you already know to contact OMIC to report claims covered under your OMIC policy, you also must advise us of any claims filed against you that are covered by another carrier. Additionally, you must notify OMIC if a professional conduct complaint is filed against you, and as soon as you become aware of any proceedings or status changes regarding your license to practice medicine; your BNDD (drug) license, privileges at a hospital, HMO, or other medical facility; or your certification by or membership in a medical association, society, or board.

You are required to notify OMIC when certain life changes occur, for instance, if you have been treated for any medical condition that might impair your ability to practice, if you have been diagnosed with any mental illness, or if you have experienced any alcohol or drug dependency problems. If you are taking time off from your practice for maternity or paternity leave, you will want to alert OMIC because you may be eligible for a suspension in coverage.

Policy Endorsements and Coverage Reviews

While OMIC attempts to accommodate its insureds and their practice needs, changes requested by insureds are not always approved due to underwriting considerations. If requests are not made in a timely manner, there is no guarantee that we will retroactively amend your policy. Please remember that only endorsements or revised policy declarations, not simply notice, can waive or change the terms of your policy.

Under certain circumstances, changes that the insured notifies OMIC of may result in the insured being reviewed for continued insurability by OMIC. When certain increases in hazard are apparent or when membership criteria are not met (for example, if an insured loses his or her license or is no longer a member of the American Academy of Ophthalmology), OMIC may discontinue providing coverage to the insured.

The consequences of not notifying OMIC of changes will vary depending on the nature of the omission and the circumstances under which the omission is noted. These range from simply updating the information in your OMIC underwriting file to possible denial of a claim, or, in extreme cases, cancellation of your policy. Our goal is to encourage our insureds to notify us of changes to information we have about them in a complete and timely fashion to avoid any gaps in coverage.

Group Policies

By Kimberly Wittchow, JD

OMIC Staff Attorney

Digest, Summer 2005

Whether you are new to a group practice or leaving a group to work for yourself or with others, you should be aware of how an OMIC group policy works and what to do if your practice situation changes.

A group that has OMIC professional liability insurance is usually issued one policy. The Declarations Page, which accompanies the policy, lists the ophthalmologists, CRNAs, optometrists, and any entities that are covered under the group’s policy. Under INSURED AND MAILING ADDRESS on the Declarations Page, the group name, or “policyholder,” is listed. This policyholder controls the group policy and is the main party with whom OMIC communicates about the policy.

Notice

Communications are often handled on behalf of the insureds of a group by the policyholder’s administrator or representative. OMIC assumes that, as a member of the group, the insured has given this representative the right to speak on the insured’s behalf regarding routine underwriting issues. While the administrator may initiate or facilitate a change in coverage, OMIC will seek the insured’s consent before changing the insured’s coverage limits, provisions, or classifications. Whenever possible, OMIC will communicate directly with an insured regarding any sensitive issues, such as licensure actions, substance abuse problems, or medical or psychiatric treatment.

Payment of Premium

Often, the business entity for the group will pay for each of the insured’s premiums under the policy. Nevertheless, each insured under the policy is considered by OMIC to “own” his or her own coverage. (Note, however, that for slot coverage for residents and fellows, the slot position, and not the individual in the slot, is the insured, and therefore the coverage is controlled entirely by the group practice.) This means that the insured is ultimately responsible for payment of his or her coverage under the policy. However, any refund of premium is credited to the policyholder, and it is the policyholder’s responsibility to distribute any refunds to individual insureds as appropriate.

Cancellation and Nonrenewal

Regarding cancellation and nonrenewal, the policyholder may request that OMIC delete an insured from a group policy. OMIC will try to get confirmation from the insured that he or she agrees with this termination of coverage. If OMIC cannot contact the insured, however, OMIC will process the termination, but will continue to attempt to communicate with the insured in order to determine whether he or she would like to remain insured with OMIC under an individual or another group policy.

Prior Acts Coverage

When joining a group, insureds may choose to purchase coverage for claims based on events which occurred before their coverage inception date under the group policy. Some groups do not allow the insured to acquire prior acts coverage under the group’s OMIC policy, while others may permit or require it.

Each insured under the group policy will have his or her own retroactive date which will reflect whether that insured has prior acts coverage. Some insureds will not need prior acts coverage because they are either new to practice or their prior acts are covered under another policy. This occurs when insureds were previously covered under an occurrence policy or bought an extended reporting period (tail) endorsement from their previous carrier. Remember that an insured’s retroactive date is usually not the same as the group entity’s retroactive date, and that the insured’s inception date may also be different from the group’s if the insured joined after the beginning of the group’s policy period.

Tail Coverage

Some groups require physicians to sign contracts when they join the group. Under these contracts, the group might require that, when a physician leaves the practice, he or she maintain coverage for the activities he or she participated in as a member of the group. This might take the form of purchasing a tail upon leaving the group, or proving that he or she maintains prior acts coverage under his or her new insurance policy after being deleted from the group policy. OMIC sends a tail offer directly to the insured upon termination of coverage. While it is ultimately the insured’s responsibility to obtain tail coverage if desired, a group may agree to pay for it. If the insured instead purchases prior acts coverage from his or her new carrier, the group might require that certificates of insurance be sent to the group periodically to ensure that the physician who left is maintaining his or her coverage for acts undertaken while with the group.