A Medical Board Investigation Handled Perfectly

By Ryan Bucsi, OMIC Senior Litigation Analyst

Digest, Winter 2007

ALLEGATION: Complaint to state medical board of loss of vision following laser treatment for diabetic macular edema.

DISPOSITION: Medical board did not pursue investigation following defense attorney’s letter of response.

Case Summary

A patient presented to an OMIC insured’s office with a visual acuity of 20/40 in the right eye and 20/60 in the left eye. The physical examination revealed clinically significant diabetic macular edema in both eyes with foveal lipid in the left eye. The ophthalmologist subsequently performed laser treatment on each eye on separate dates. At the follow-up examination, the patient did not exhibit any change in visual acuity or complain of any loss of vision. The diabetic macular edema resolved in the right eye but persisted in the left eye, so the surgeon performed another laser procedure.

The insured’s associate evaluated the patient at her follow-up visit two months later. Although the patient had never called to report any visual acuity loss, she now said that she had not been able to see well since the second procedure. Her visual acuity was 20/400 in the right eye and count fingers in the left eye. She was diagnosed with severe diabetic macular edema in both eyes with possible macular ischemia. The associate recommended a repeat fluorescein angiography to assess the perfusion status of the maculae and to evaluate the vascular status of the retina in each eye.

The patient chose not to return to the insured. The insured then advised her in writing that the advanced state of her condition required that she either come in for a follow-up appointment or see another ophthalmologist; he warned that lack of care could further jeopardize her vision. The patient reportedly sought care with another ophthalmologist as advised.

Analysis

The patient filed a complaint with the state medical board alleging that her compromised vision in both eyes was a result of the second laser treatment. The insured and his attorney worked together to craft a response to the medical board complaint and an expert witness was retained to evaluate the care. The physician’s letter to the medical board started out by admitting that the laser treatment did indeed cause destruction of the macular retinal tissue responsible for central visual acuity but that it could do so only in the treated eye. Notably, the patient had complained of delayed bilateral visual loss, for which another cause needed to be found.

The retained expert supported the physician’s care, opining that the procedures were indicated and appropriate for the patient’s macular condition and that there was no objective or significant change in her visual acuity immediately following either of the treatments. The expert felt that the most likely cause of the patient’s vision loss was her underlying diabetic retinopathy, which had progressed rapidly due to other factors such as duration of her diabetic condition, degree of blood sugar control, underlying vascular disease, compromised renal function, and anemia. This worsening of the patient’s diabetic retinopathy may have led to macular ischemia and progressive leakage of fluid and lipid from incompetent diabetic macular blood vessels.

Risk Management Principles

This case exemplifies how a medical board investigation should be handled. Even though the ophthalmologist was confident that he had met the standard of care, he immediately reported the matter to OMIC’s claims department. The OMIC litigation specialist for the insured’s state promptly referred the case to an attorney, who in turn retained an expert. Within one month of the date of the medical board letter of investigation, the OMIC attorney had worked with the insured to draft a response. Furthermore, the expert signed an affidavit supporting the physician’s care; this affidavit was attached to the letter of response. The medical board decided not to pursue the matter and concluded its investigation. The insured’s willingness to cooperate and work with the OMIC-appointed attorney to craft an effective response was a key factor in averting a potentially costly and time-consuming medical board investigation.

Medicolegal Implications of Fluorescein Angiography

By Arthur I. Geltzer, MD

Digest, Spring, 1991

A large number of ophthalmologists consider baseline fluorescein angiography an unnecessary procedure given the threat of serious complication and even fatality, according to an informal survey of 670 retinal specialists. A majority of those surveyed said they would perform a baseline angiography study only if they clinically suspected choroidal neovascularization or diabetic retinopathy.

Survey Response

Problems with fluorescein angiography have come to light in recent years because of malpractice litigation questioning the appropriate timing and initiation of therapeutic measures following fluorescein administration. In 1990, OMIC received responses to a written questionnaire mailed to 1,540 ophthalmologists identified by the American Academy of Ophthalmology as retinal specialists to evaluate their practices and views regarding fluorescein angiography as a diagnostic tool. A relatively high response rate of 42% was obtained by using a simplified questionnaire which did not request a yearly rate computation of complications. Thus, the resulting information is not presented as a scientific study, but rather to provide guidelines to OMIC insureds and the ophthalmic community about the indications, timing and potential risk management issues involved with fluorescein angiography and laser treatment.

Complications Cited

Respondents to the informal poll reported a variety of complications associated with fluorescein angiography including syncope, myocardial infarction/cardiac arrest, skin slough, anaphylaxis, asthma, hypotension, seizures, respiratory arrest, severe Meniere’s attack, and in some cases death.

Given the possibility of serious complications, most respondents indicated they would question performing angiography as a baseline study unless the patient presented with evidence of choroidal neovascularization.

Emergency Capabilities

The presence of a physician in the office during fluorescein angiography appears to be a widely accepted practice among almost all respondents. Those who do not require it are frequently in a hospital setting where emergency medical care is readily accessible. In fact, 96% of respondents reported having emergency capabilities available, the largest consensus in the survey. While most respondents indicated that a certified ophthalmic technician may not be required to perform an angiogram, they do believe the procedure should be supervised by a retinal specialist who is qualified to perform laser therapy if indicated. Most agree that recorded photographs would be very beneficial and should be obtained.

Communicating Test Results

After the clinical diagnosis of choroidal neovascularization in age-related maculopathy is made, a large majority of ophthalmologists polled indicated they would perform an angiogram, communicating the results to the patient and/or referring physician within 72 hours. Because of the potential rapid progression of choroidal neovascularization, most retinal specialists consider laser therapy to be urgent in treatable cases. The ophthalmologist who procrastinates, either in fluorescein diagnosis or therapeutic measures, may face increased liability exposure in addition to potentially increasing the likelihood of a disappointing outcome.

Risk Management Considerations

Since the results of this informal survey are not presented as pure scientific data, they are not intended to suggest a standard of care. However, readers may wish to consider the following risk management implications of this poll:

While fluorescein angiography is an important diagnostic tool for the ophthalmologist, its use as a baseline indicator in diabetic retinopathy or age-related maculopathy may not be appropriate unless the patient shows signs or symptoms of significant diabetic retinopathy, loss of vision, Amsler grid pattern changes or choroidal neovascularization.

As a general rule, a physician should be present in the office during fluorescein administration and emergency equipment should be available, including pharmacologic agents.

Finally, patients who have been clinically diagnosed with choroidal neovascularization should receive prompt treatment by a retinal specialist, including fluorescein angiography and laser therapy if indicated.

Preop Planning Can Prevent Mix-Ups in the OR

By Oksana Mensheha, MD

Argus, March, 1993

Among a small group of ophthalmologists I talked with, more than half acknowledged that they had either personally operated on the wrong eye or knew someone who had. Their experiences ranged from performing a cataract extraction on the wrong eye and doing an esotropic procedure on an exotropic child to removing the wrong eye for a malignant melanoma. Surgeons who have not actually operated on the wrong eye admit they have come close.

What can we do to prevent such mix-ups from occurring?

When doing cataract surgery, I find it helpful to record the A-scan by itself for the eye to be operated on and to post this on the wall of the OR. I record the results for the right eye on the top half of a sheet of paper:

Kod=

ALod=

Order Lens Power od=

I record the results for the left eye on the bottom half of another sheet of paper. I try to avoid recording both A-scans in the same place because it can be confusing. Of course, both eyes can be scanned at the same time, but it takes little effort to record the results separately.

I also find it helpful to bring my office chart into the OR. My office chart documents the scheduling of the surgery and has multiple indications of which eye is to be operated on. If I have a chance to see the patient preoperatively, I try to make certain the dilated eye is the preop eye noted in my office record. I also try to verbally confirm this with the patient. Another safeguard some surgeons use is to preoperatively mark the eye to be operated on with a marking pen.

Performing the wrong procedure on a strabismic child can also prevent significant problems. Some children’s eyes can appear to be straight under general anesthesia, adding to the confusion. If possible, try to examine the child before the anesthesia. In the case in which the ophthalmologist performed surgery for an esotropia instead of an exotropia, the child was wearing the wrong name tag, and the operating rooms had been switched.

Such a mix-up might be avoided if the parents identify the child prior to surgery, or if preop photographs are available for each child scheduled for surgery that day. Once in the OR, a quick check of the photos together with the office record will confirm that the correct child is in the OR, receiving the proper surgery.

The most serious event I heard about was the removal of a healthy eye instead of an eye with melanoma. The diseased eye subsequently was removed. Again, bringing well-documented office records into the OR might have prevented this occurrence. Dilating the proper eye as well as marking an “X” above the eye preoperatively also might have helped. Finally, with irreversible procedures such as enucleation, consider examining the eye with indirect ophthalmoscopy before proceeding.

No system is foolproof. However, referring to your office record when you are in the OR, after ensuring that the record matches the patient to be operated on, can be a tremendous help in avoiding surgery on the wrong eye.

Risk Management Issues in Medical Retina Disorders

By Jerome W. Bettman Sr., MD, and Monica L. Monica, MD, PhD

Digest, Fall, 1994

Malpractice suits involving medical disorders of the retina have become more common, specifically those involving diabetic retinopathy and macular degeneration. Informed consent plays a major role in helping retina patients understand the consequences of failing to receive treatment and accept the sometimes less-than-perfect results of treatment. The following case will help illustrate the problem.

Diabetic Retinopathy

Mrs. Jones was a 65-year-old diabetic who presented to an ophthalmologist complaining of a fuzzy spot in her right eye upon reading. She had been an insulin-dependent diabetic for more than 15 years and was well-controlled on medication. On examination, the ophthalmologist discovered metamorphopsia on Amsler grid testing, and exudates and hemorrhages in the perimacular area of the right eye. A fluorescein angiogram was performed which delineated the problem vessels. The ophthalmologist told Mrs. Jones that leaking blood vessels in her eye were causing the blurred spot and explained how a laser could be used to seal off the leaking blood vessels and help her vision.

Laser therapy was successfully performed and eventually the exudates resorbed and the hemorrhage resolved; however, Mrs. Jones still complained about a blurred spot in her right eye upon reading. She was told that the laser had created a scar and that this scar was causing some visual disturbance, but that her initial problem leaking blood vessels had been solved by the laser. Mrs. Jones did not see it that way, and she sued the ophthalmologist.

This case illustrates a few points. One is that disorders of the retina can be complicated and difficult for patients to understand. Videos and patient reading materials may be helpful, but the patient needs to be given ample time to review these materials and to ask questions. Secondly, patients often do not understand the consequences of laser treatment, or they honestly do not recall those complications that might destroy vision. 1,2,3

For many, the idea of treatment is synonymous with cure. Mrs. Jones was very upset to discover that she still had blurring from macular degeneration. Many patients view the laser as the restorer of perfect eyesight when that may be far from the case. It may be helpful to have the patient write in the chart what he or she understands the possible result of laser therapy to be. This is evidence that cannot be denied in a courtroom.

Retinopathy of Prematurity

For several decades, retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) has been the source of numerous malpractice suits, although there is little doubt that some ROP cases were misdiagnosed and were actually Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy, or Coat’s Disease, Eales Disease, macular ectopia, and the like.

Some historical perspective on this problem is instructional. Early ROP claims were based upon the fact that more than 40% oxygen was given to the neonate. At the time, this was the upper limit that was considered appropriate, and any greater concentration constituted malpractice. This arbitrary limit had no basis in scientific fact. As a result, oxygen was severely curtailed and cerebral palsy, respiratory distress syndrome, and death increased in incidence. It was then decided that oxygen should be administered in whatever concentration and duration was necessary for the neonate’s survival. The incidence of malpractice suits increased again. It is now generally concluded that the prematurity itself is the most significant etiological agent. In addition to the oxygen, a number of factors play a role in the development of retinopathy of prematurity, i.e., pH, CO2, prostaglandins, Vitamin E, and others. If oxygen is used only in necessary amounts, it should not be the basis for a suit.

A major catalyst in ROP claims is failure to adequately communicate the potential problems the baby may face even after treatment. Parents are often stressed by the illness of the baby and do not adequately comprehend all the details at the time. This has led to problems with follow-up on the babies, especially for eye checks. It is helpful to involve the entire nursing team in any discussion of the neonate’s problems and the protocol for follow-up. Hearing these messages repeated by the various health personnel involved in their baby’s treatment will reinforce for the family the importance of follow-up care.

Timely Follow-up Crucial in ROP Cases

Progressive retinopathy of prematurity was once an untreatable condition. Cryotherapy to retard the progress of the disease was first proposed in Japan in 1972. Because of the lack of convincing data and complications of treatment in some cases, cryotherapy was not strongly advocated in the United States. The cryo-retinopathy of prematurity study demonstrated an unfavorable outcome in untreated eyes of 43% compared to 21.8% in treated eyes.4

This positive finding reinforced the need for ophthalmologists to detect and carefully follow babies with retinopathy of prematurity changes even after discharge from the neonatal ICU. Babies with so-called threshold disease (defined as five or more contiguous or eight cumulative 30 sectors, or clock hours, of Stage III retinopathy of prematurity in zone one or two in the presence of “plus” disease) are felt to be candidates for cryotherapy. Failure to treat may result in litigation. Timely follow-up of these infants at regular intervals is crucial.

Retinal Tumors

Misdiagnosis of a retinal tumor has accounted for a low proportion of malpractice suits involving medical retina problems. Melanomas are sometimes diagnosed as retinal detachments. Infrequently, claims have arisen because a large subretinal hemorrhage was misdiagnosed as a melanoma and the eye was enucleated. Ophthalmologists should not be afraid to seek second opinions on those cases which do not conform to the usual axioms of diagnosis.

Conclusion

So often, ophthalmologists focus their attention on surgical cases and complications. While surgical incidents do make up a large part of malpractice claims, claims involving medical diagnoses and treatment, especially of retinal disorders, are becoming more common.

Notes:

1. Priluck IA, et al. What Patients Recall of Preoperative Discussion after Retinal detachment. Am J Ophthal. 1979; 87:620.

2. Robinson G and Merav A. Informed Consent: Recall by Patients Tested Postoperatively. Ann Thorac Surg. 1976; 22:209.

3. Leeb D, et al. Observations on the Myth of “Informed Consent.” Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976; 58:280.

4. Tasman W. Threshold Retinopathy of Prematurity Revisited. Arch Ophthal. 1992; 110:623.

Medicolegal Implications of Using Off-Label Drugs and Devices

By E. Randy Craven, MD, and Elizabeth C. Moran, JD

Digest, Winter, 1996

Most physicians have heard these words: “Doctor, isn’t there anything else you can do? Some new treatment you can try?” Patients often perceive “new” treatments as better or less problematic than existing treatments and pleas for something “new” are particularly understandable when patients are faced with a terminal condition or loss of vision. Physicians generally look for proven treatments that will give their patients the best results with the least side effects. However, because of the tremendous psychological leverage of offering something “new,” physicians might be tempted to try unproven treatments to keep up with market forces. A good example of how market forces lead to such decisions might go something like this: “Mrs. Jones, you have the privilege of being in the right place at the right time. I am excited to inform you that I use the latest technology. The old method of correcting myopia is out and my new technique is in. In fact, because of my commitment to stay on the cutting edge, the laser I will be using to reshape your cornea was designed by me with the help of an engineer. This laser will correct your myopia in minutes.”

What assurance does Mrs. Jones have that the laser developed by her ophthalmologist is safe? Is it prudent for physicians to develop their own equipment or drugs for use on their patients? Who or what regulates physicians who do so?

Regulation of Physicians’ Practices

Production, sale, and clinical research of new drugs and medical devices are subject to regulation by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Physicians and patients are protected to some degree when they use drugs or devices that have undergone the scrutiny of the FDA and received approval for marketing and sale. The known indications, hazards, and adverse effects of the approved device or drug are required to be included in the product labeling. The FDA can restrict the ability of a company to sell, manufacture, or import a drug or device and can impose a variety of other protective measures.

Ordinarily, physicians are not directly regulated in their use of drugs and devices in day-to-day practice but are expected to practice in a manner that is designed solely to insure the well-being of the patient. Unless a physician is himself marketing or selling a drug or device, or acting as an investigator in clinical research, the FDA generally does not oversee or interfere with a physician’s individual practice decisions.

It is a different matter when the physician is conducting clinical research. Research activity occurs when the clinician conducts a “systematic investigation” designed to develop or contribute to “generalizable knowledge” such as by testing a hypothesis, drawing conclusions, and developing a base of knowledge from the results, especially concerning safety or effectiveness of the product.

If a practicing physician departs from usual (standard) treatments for an individual patient, such as by using a self-made device, a modified device, or a marketed drug for an off-label use, such use does not in and of itself constitute “research.” However, the non-standard treatment might constitute a deviation from accepted standards of medical care. The standard of medical care, which is based upon what reasonable physicians in the same specialty would do at the same time under similar circumstances, is overseen by state and local medical boards, and indirectly, by malpractice lawsuits. Issues of deviation from standards of care are usually raised by patients and/or other practitioners filing a complaint with their state or local medical board or by patients bringing malpractice lawsuits. The medical board also may be informed of aberrant practice styles by federal agencies, such as the Health Care Financing Administration and Medicare Peer Review Organizations.

In addition, local hospitals and clinics oversee standards of medical practice through credentialing, peer review, and quality assurance procedures, which involve investigations of standards of care, identification of deficiencies, and establishment of minimum qualifications for privileges. This is why malpractice insurance companies request information relating to licensing sanctions, peer review proceedings, and denial or surrender of hospital privileges.

So Mrs. Jones is protected by community standards, state and local agencies and institutions, and to a lesser degree, by agencies of the federal government.

Physician Practice versus Investigational Use

A physician may manufacture his or her own equipment or devices solely for his own use in his practice, and may use approved products for non-approved (off-label) applications. In fact, off-label use of medication is quite common. Distinguishing off-label use of drugs or devices as part of a physician’s practice from “experimental” or “investigational” use may be difficult at times. If the new use is based on firm scientific rationale and sound medical evidence, and is not for the purpose of developing information about safety or efficacy (for example, to support a request for FDA approval of the new use or to support advertising of new uses for the product), the use generally will qualify as “the practice of medicine” rather than “investigational use.”

However, if the physician is gathering new information on multiple patients, particularly for publication purposes or to obtain approval for a new device or new use, it is probably considered research, and the physician must comply with the panoply of federal statutes and regulations governing all aspects of approval of new drugs and devices, including numerous requirements for the protection of human subjects in research. In most cases, the practitioner will be required to obtain approval from his or her local Institutional Review Board (IRB), a committee that operates under HHS and FDA regulations for the purpose of protecting the rights of research subjects. The FDA will not accept research data in support of a new drug or device application unless the research protocol and consent documents have been reviewed and approved by an IRB. Similarly, peer reviewed journals usually require documentation of IRB approval before research results will be accepted for publication.

The FDA does have the right to request tracking of marketed products and, although off-label uses in medical practice are not generally regulated, the FDA can disapprove an existing product, require additional warnings, and/or request a recall of a product if it is not happy with off-label uses of the product. Otherwise, regulation of a physician’s medical practice generally falls under the jurisdiction of the state and local agencies previously discussed.

Liability and Insurance Issues

If a physician develops a new device, such as a new ultrasound for phacoemulsification to use on patients in the office, he or she may well face additional liability exposure for problems resulting from the use of the device. Injuries caused by the use of non-approved devices and drugs generally fall within the scope of malpractice and general liability coverage, but a physician may be exposed to personal risk as well if the insurance policy does not cover the liability associated with such uses.

For this reason, it is a good idea to contact your professional liability carrier about potential liability exposure if any of your practice activities involve the use of a self-made instrument or off-label use of drugs or devices regardless of whether they have gone through IRB approval. OMIC, for example, has carefully considered the use of the excimer laser in photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) and laser assisted in-situ keratomileusis (LASIK) and has developed internal guidelines intended to help reduce the increased professional liability and exposure to claims associated with their use.

Off-label applications of drugs also increase the potential for liability, although many drugs are widely used this way. A good example is mitomycin-C (Mutamycin) for glaucoma surgery. Mitomycin-C is FDA approved “for the use of disseminated adenocarcinoma in conjunction with other approved chemotherapeutic agents.” There is no mention of using this drug for pterygia or glaucoma surgery, and there is a long list of side effects for this drug, including pulmonary toxicity that does not appear to be dose related. Nevertheless, glaucoma surgeons are using this medication with increasing frequency, and even a few general ophthalmologists are using it to prevent the recurrence of pterygia following excision.

OMIC has considered the use of mitomycin-C and other off-label drugs (such as cyclosporin drops) and has this general recommendation:

When using a new or old drug in an approved manner, proceed with a green light. If it is an existing drug used in a non-approved manner (off-label), first consider whether its use poses significantly increased risks to the patient. Second, consider whether its use can be expected to bring good results without a higher complication rate. If it presents no more risk to the patient than that of daily living, proceed with its use; for example, the use of aspirin for anticoagulation after a central retinal vein occlusion. If there is an increased risk to the patient, ask yourself if at least a reasonable number of physicians in your specialty are using the treatment; that is, have peer reviewed articles been published supporting the use of the new treatment and is the treatment being used by a reasonable number of other practitioners with the same level of training as you?

Ophthalmologists are considered medical “specialists” and in most cases are held to a “national” rather than “local” standard of care. The same is true of subspecialists in various areas of ophthalmology. An ophthalmologist may face increased liability for off-label uses if a reasonable number of similar specialists or subspecialists are not using the same new treatment. An ophthalmologist whose patients experience more problems with off-label use of a medication than they would with standard methods of treatment might well be subject to professional criticism, and thus be exposed to malpractice liability and potential licensure or credentialing actions.

Additional Precautions

When considering new techniques, new devices, or new uses for approved drugs, practitioners need to think about taking additional measures to protect themselves as well as their patients. If you select a treatment for an individual patient with the intent that it will enhance the patient’s well-being, and there is sound medical evidence supporting the treatment, you are likely to be on solid ground. In such cases, FDA regulation is generally not controlling, and you probably will not need IRB approval unless the treatment so departs from standard practices that it may be considered experimental or investigational, or it presents significantly increased risks for the patient, and/or you wish to use the information for study purposes.

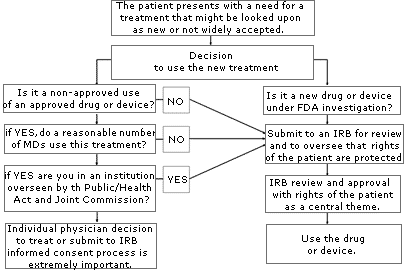

If you are uncertain about whether your use of a treatment or device might be considered “investigational” or “experimental,” consult your local IRB. An IRB is usually available at your local institution (some regional IRBs also exist) to review your proposed use and determine if it constitutes “research” requiring IRB approval. Similarly, if you are unsure whether the treatment has sufficient peer support or is simply too new, or if the literature is unclear, consider going through an IRB to help you with your decision. The flow diagram set forth on page A-78 may help you through the process of determining if you should submit your treatment proposal for IRB review.

Anytime you are considering unapproved uses of a device or drug, the informed consent process and its documentation, including treatment alternatives, should be thorough and specific in case you are later called upon to defend your decision to use non-standard treatments. If you have a specific area of concern, contact OMIC’s Risk Management Department for further information or referral to the appropriate resource or agency.