Risk Management

| << Back |

Surgical Team Briefings Reduce Malpractice Risks

By Anne M. Menke, RN, PhD

OMIC Risk Manager

Digest, Fall 2011

Communication breakdowns are the primary cause of 70% of serious adverse events reported to The Joint Commission (TJC).1 Nowhere is clear and consistent communication more important than in the operating room. To facilitate the exchange of critical information among surgical team members, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced a basic surgical checklist in 2008, proposing it as a method to “help ensure that teams consistently follow a few critical safety steps and thereby minimize the most common and avoidable risks endangering the lives and well-being of surgical patients.”2 The checklist divides surgical care into three phases: sign-in before anesthesia, time-out before incision, and sign-out before transfer from the OR to the post-anesthesia recovery room (PACU).

In addition to the elements of the universal protocol (identification of the patient, procedure, site, and side), the WHO time-out and sign-out include briefings from the surgeon, anesthesia provider, and nurse that—if consistently implemented—would prevent many malpractice claims reported to OMIC. The surgeon addresses critical or unexpected steps in the procedure, its planned duration, and the anticipated amount of blood loss. The anesthesia provider relates any patient-specific concerns such as cardiopulmonary diseases, arrhythmias, difficult airway, etc. The nurse confirms the sterility of the instruments and covers any equipment issues. This article discusses some ophthalmic-specific adaptations of the WHO surgical checklist prompted by OMIC’s claims experience. We were aided in our analysis of surgical team briefings by eye surgeons from Rush University Medical Center. OMIC Directors Steven V. L. Brown, MD, and Tamara R. Fountain, MD, along with their colleagues Jack Cohen, MD, Randy Epstein, MD, and Diany Morales, MD, presented their thoughts on critical steps in some ophthalmic surgeries to nurses and technicians who attended the 2010 ASORN annual meeting. With their permission and our thanks, some material from their talk is presented here, and supplemented with OMIC closed claims data and guidance from other resources.

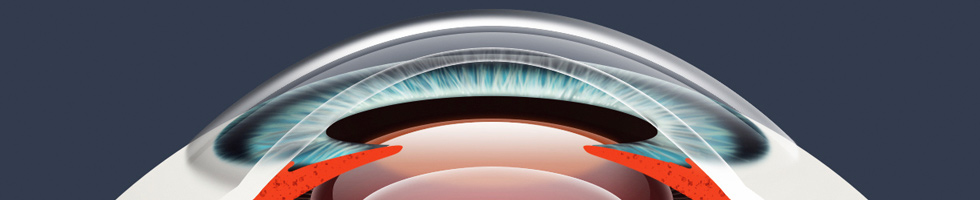

Corneal Transplant Surgery

When all corneal transplantations involved performing a penetrating keratoplasty (PK) to place fullthickness grafts, there was less chance for confusion. In the early 2000s, ophthalmologists developed ways to remove and replace only the part of the cornea that was diseased or damaged. Dr. Randy Epstein explained that the corneal transplant surgeon now needs to verify the procedure and tissue type in the team briefing. The names for the surgical techniques can be confusing for team members unfamiliar with corneal anatomy but must be understood to ensure that the proper instruments and donor tissue are available. PK requires fullthickness donor tissue, while deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK), Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK), and Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) use only partialthickness corneal donor tissue. Some surgeons use a femtosecond laser rather than a metal trephine to create specially shaped overlapping edges in the patient and the graft that create a tighter fit and require fewer sutures, so laser safety measures must be implemented. To comply with tracking regulations and prevent mix-up and contamination, the surgeon also should discuss donor tissue accountability measures that need to be followed when human cells, tissues, and cellular and tissuebased products (HCT/P) are implanted; these apply to amniotic membrane grafts as well as to corneas. Careful discussion of these steps helps prevent corneal graft failure.3

Glaucoma Surgery with MMC

Dr. Steven Brown educated nurses on current medical and surgical treatments for glaucoma and complications of trabeculectomy. Nurses need to be prepared to help the surgeon manage intraoperative complications, which occur in 11% of trabeculectomy cases. The most serious ones are suprachoroidal hemorrhage, considered an emergency, and a conjunctiva buttonhole. The glaucoma surgical team needs to be aware of the use and risks of Mitomycin-C, a chemotherapeutic medication used off-label not only in glaucoma procedures but also in many other types of ophthalmic surgery to reduce inflammation, prevent scarring, and decrease the likelihood of recurrence of conditions such as pterygium. Small sponges are soaked in the MMC and then placed in or on the eye. MMC can cause significant ocular complications, so the number of sponges, as well as the dosage, location, and duration of MMC application, needs to be specified and verified in the standing orders, surgical briefing, sign-in, and sign-out. Medical malpractice lawsuits have been filed after pieces of sponge material were left in the eye, resulting in more exposure to MMC than intended. Depending upon the ASC or hospital policy, facilities may be obliged to report a retained sponge case to their accreditation agency as a sentinel event. Some facilities have been fined by state licensing boards for retained sponges. Prevention of retained MMC sponges has proved challenging due to their size and tendency to shred. See the Closed Claim Study for details of an OMIC case and risk management recommendations on ensuring safe removal of these sponges. Staff safety is also a concern when MMC is used, as it is a toxic and potentially hazardous drug. The American Society of Ophthalmic Registered Nurses (ASORN) has prepared a laminated card detailing the “top tips for safe handling, use, and disposal” of MMC. ASCs would be well-served to obtain a copy and post it in the medication preparation room.

Oculofacial Surgery in the Setting of Anticoagulants

Dr. Tamara Fountain focused on what she termed “the art of managing the risk of perioperative systemic anticoagulation.” Patients presenting for oculofacial procedures, which have a higher risk for hemorrhage than other ophthalmic surgeries, are often taking medications prescribed by their primary care physician or cardiologist, such as aspirin, warfarin (Coumadin), and clopidogrel (Plavix). These drugs are intended to prevent heart attacks and strokes, and may need to be taken for as long as a year following procedures such as cardiac stents to prevent death. In addition to prescription drugs, many patients manage their aches and pains with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines, some of which have blood-thinning properties. Finally, patients may supplement their diets with the three g’s (garlic, ginger, and ginkgo biloba) as well as feverfew and grape seed, all of which can increase bleeding. There is no clearcut consensus within the ophthalmic community on whether to stop or continue anticoagulants before ocular procedures. Dr. Fountain explained that rational decisions need to be made in each case by weighing the relative risks of each intervention. Perhaps the most important step in the risk management process is a candid discussion with the patient about the risks of continuing or stopping anticoagulation; the patient must understand and accept the increased risk of either approach. The surgical team should address the specific procedure’s risk of hemorrhage and the patient’s relative risk of a thromboembolic event during the sign-in before anesthesia and as part of the team briefing at both sign-in and sign-out. If the surgeon and physician who prescribed the anticoagulant decided to stop it, the team needs to ensure that the patient did indeed stop it, then check a preoperative INR blood test for patients on warfarin, monitor for signs of a thromboembolic event, and review with the patient when the medication should be restarted. If anticoagulants are continued during ocular surgery, bridge medication therapy may be indicated, pain and blood pressure need to be well controlled, and fibrotic agents must be available. Nurses in the OR and PACU, and the patient, need to be reminded to watch for signs and symptoms of hemorrhage, such as subcutaneous hematoma, increased and prolonged swelling, asymmetry, and orbital hemorrhage, which could lead to a compromised surgical result, vision loss, and exsanguination. OMIC has had claims involving both thrombolic events and hemorrhage that resulted in significant patient harm and large indemnity payments. Careful collaboration with the primary care physician or cardiologist about the decision to continue or stop medications and well-planned teamwork during the procedure could help prevent such claims.4

Retina Surgery with Gas

Surgery to treat retinal detachment, diabetic retinopathy, and proliferative vitreoretinopathy often involves the use of a gas to tamponade the retinal hole. The colorless, odorless gas is supplied at 100% in cylinders and must be diluted with filtered air to the percent ordered by the surgeon in order to achieve the therapeutic effect without causing serious harm to the patient’s eye. Dr. Jack Cohen explained that if the gas delivered is above a certain level, its volume can increase, leading to elevated intraocular pressure, possible central retinal artery occlusion, and loss of vision via many mechanisms. The surgical team needs to know the concentration and work together to ensure that the dilution process is correctly followed. Multiple steps are critical. Once the tubing from the gas cylinder to the syringe has been “rinsed” of air, the syringe is filled about half way with pure gas. The tubing connecting the syringe to the gas tank is now disconnected and the syringe stopcock is turned toward the syringe so none of the gas leaks out of the syringe. Next, the surgeon and nurse agree on the concentration of gas for the patient. The nurse repeats the concentration back to the physician so each can confirm the desired amount. The surgeon watches the scrub nurse push the pure gas from the syringe to the desired percentage labeled on the syringe. The physician then watches the nurse dilute the pure gas by pulling filtered air into the syringe to the labeled line. The syringe stopcock is now turned toward the syringe to prevent losing any of the diluted gas. At this point, the gas has been diluted correctly, and both the physician and nurse have witnessed and verified the dilution process. This communication is especially important when there is a new member of the team. OMIC settled a case where the ophthalmologist ordered a 15% concentration. His usual assistant was not available, so the hospital assigned another ophthalmic nurse, who did not tell the team that she was unfamiliar with the process of diluting gas. The surgeon did not watch the dilution process, but did ask for oral confirmation of the percentage, which the nurse stated was 15%. The patient developed a significant rise in intraocular pressure after the procedure, leading to damage to the optic nerve and NLP vision. The nurse informed the surgeon the next day that she had not diluted the gas at all. Defense experts supported the surgeon’s attempt to confirm the amount, but felt he could have prevented the nurse’s error from impacting the patient by watching her dilute the gas or preparing it himself. OMIC contributed 35% toward the settlement on behalf of the surgeon.

Strabismus Surgery Briefing

There are a number of issues specific to strabismus surgery that warrant a team briefing. Dr. Diany Morales first pointed to the need to verify not only the correct patient and eye as in all surgeries but also the correct amount of surgery and the correct muscle. She advocates having the office record available in the OR and writing the operative plan on the white board so it is visible to the surgeon (“RMR recession 6 mm, RLR resection 8 mm”). Muscle confusion can be caused both by disorientation from sitting at the head of a patient as well as globe rotation from deep anesthesia. Safeguards include checking the distance of the insertion site to the limbus. Globe perforation is a known risk and clear two-way communication is vital. During the briefing, the surgeon reminds OR staff to check before making any adjustment to the bed, drapes, or IV, and states that she will announce the critical moment when she is about to pass scleral sutures. The final key issue to address is anesthesia risk, as many patients undergoing strabismus surgery are children with issues such as prematurity or comorbidities, and general anesthesia is often required. Patients undergoing strabismus surgery are at higher risk for two potential complications: bradycardia and malignant hyperthermia. The surgeon prepares the team to manage bradycardia by announcing when the rectus muscle will be under traction, as this can provoke the oculocardiac reflex, and asking the anesthesia provider to announce if the heart rate slows to an unsafe level so the surgeon can ease the amount of traction. Like untreated bradycardia, malignant hyperthermia is potentially fatal, even though better recognition and treatment has decreased the mortality from 70 to 10%. It is a metabolic disorder characterized by extreme heat production and muscle breakdown that is known to be more common in patients with strabismus. The team must have the appropriate equipment and be briefed on prompt recognition and management. Surgeons have a leadership role to play in briefing team members and preventing potential errors from reaching the patient. They can also model a commitment to patient safety by using surgical checklists and team briefings for all procedures, regardless of location.

1. “Improving Handoff Communications: Meeting National Patient Safety Goal 2E.” Joint Perspectives on Patient Safety. JCAHO, 2006; 6(8):9-15.

2. World Alliance for Patient Safety. “WHO Surgical Safety Checklist and Implementation Manual.” World Health Organization, 2008; www.who.org, accessed 10/31/11. This list was enhanced by the Assn of PeriOperative Registered Nurses (AORN) to include a pre-procedure check-in that helps facilities comply with TJC universal protocol requirements and national patient safety goals.

3. See“Current Good Tissue Practices for Human Cell, Tissue, and Cellular- and Tissue-Based Products” at www.fda.gov.

4. See “Hemorrhage Associated with Ophthalmic Procedures” at www.omic.com for a detailed discussion of anticoagulants and measures needed to address hemorrhage.

Please refer to OMIC's Copyright and Disclaimer regarding the contents on this website