Risk Management

| << Back | Download |

Misunderstanding Common in Consent Discussions

Anne M. Menke, RN, PhD, OMIC Risk Manager

Anne M. Menke, RN, PhD, OMIC Risk Manager

Informed consent laws in most states require physicians to advise patients of their condition, the proposed treatment, and the risks, benefits, and alternatives of the procedure, including no treatment. The standard of what to disclose is usually what a “reasonable layperson” would want to know before agreeing to undergo surgery. The plaintiff in a lawsuit for lack of informed consent needs to prove that he would have refused to consent if the surgeon had advised him of a risk he considered “material” to his decision-making process. As the following claim shows, ophthalmologists and patients may have very different understandings of what information is needed.

It was not surprising that a patient who suffered intraoperative complications filed a lawsuit after undergoing four additional surgeries. The claims made in the lawsuit were fairly common ones for ophthalmic surgery. The plaintiff alleged that the cataract procedure was not necessary, that his physician did not obtain his informed consent, and that the intra- and postoperative complications were poorly managed. The initial defense evaluation supported the physician’s care. The prior medical records refuted the allegation of unnecessary surgery, as they chronicled slowly worsening vision that was no longer corrected by glasses or contact lenses, culminating in a referral to the defendant ophthalmologist for cataract surgery. Challenging the claim of lack of informed consent seemed similarly straightforward: the eye surgeon had documented a discussion of risks and benefits, and the plaintiff had signed a detailed, procedure-specific consent form in the physician’s office as well as a surgery center form that briefly listed risks that included blindness. Finally, expert witnesses supported the ophthalmologist’s management of the initial complication—intraoperative floppy iris syndrome, which at the time of the surgery did not even have a name yet—as well as its sequelae (rupture of the posterior capsule, iris defect, glare, and retinal detachment).

As the investigation of the suit proceeded, the lack of informed consent allegation became central, and information emerged that helps illustrate the problem some patients encounter during consent discussions. The plaintiff acknowledged in his deposition and in court that he had, indeed, read and signed the cataract consent form. Nonetheless, he insisted that the crucial piece of information that formed the basis of his decision to agree to surgery was not in the form itself. It was instead the ophthalmologist’s response to questions about the rate of complications that “there’s hardly anything we can’t fix.” The plaintiff maintained, again and again, that without such reassurance, he would not have consented to the surgery and without the surgery, he would not have suffered harm. The ophthalmologist adamantly denied making any such statement. He remembered instead that the plaintiff wanted to have a sense of the frequency of complications and that he gave him an estimate of the more common ones. The plaintiff refused to dismiss the suit and the surgeon refused to settle, so the case proceeded to a jury trial. The trial monitor felt that the key moment came when the defense attorney elicited an admission from the plaintiff that just three months before his surgery, he had served as the attorney in a lawsuit against another ophthalmologist for lack of informed consent for cataract surgery, a role that required him to have extensive knowledge of the risks of that procedure. The jury returned a defense verdict after only an hour of deliberation.

Why don’t patients understand risk information?

It is tempting to dismiss this malpractice claim as yet another example of a frivolous lawsuit. While the defense verdict was appropriate, there are important lessons to be learned from this claim. First, the plaintiff no doubt suffered while dealing with the complications and five surgeries, despite his final uncorrected visual outcome of 20/30. Many patients who experience complications conclude that the surgeon must have done something wrong, and ophthalmologists would be well-advised to proactively address this issue with such patients. An even more compelling interpretation comes from the field of “health literacy.” While the plaintiff was an intelligent and experienced litigator, when seated across from the surgeon during the consent discussion, he was simply a patient whose fears may have impaired his ability to listen, reason, and make decisions. According to the National Patient Safety Foundation (NPSF), “health literacy—the ability to read, understand, and act on health information—is an emerging public health issue that affects all ages, races, and income levels.”1 The NPSF asserts that the health of some 90 million people in the United States may be at risk because of such difficulties. Studies of this issue show that most patients, even those like this plaintiff with a high literacy level, struggle to understand healthcare information and that those with limited reading skills or difficulty understanding mathematical concepts are particularly challenged. Low health literacy appears to be at the root of noncompliance and many medication errors and leads to higher healthcare costs and poorer outcomes. A review of the last five years of closed malpractice claims suggests it may also be a driving force in lawsuits alleging lack of informed consent. This issue of the Digest will present the results of this study of OMIC claims and make recommendations for improving patients’ ability to fully engage in the informed consent process.

Analysis of informed consent claims

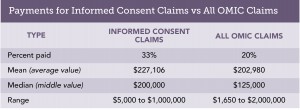

Malpractice claims regularly challenge the adequacy of the consent process. To determine the frequency of these claims and the forces behind them, lawsuits and claims that closed between January 1, 2009, and August 31, 2014, were reviewed. They were classified as “informed consent claims” if the criticism about consent formed an important part of the plaintiff’s case, even if this was not the sole or primary allegation. This contention was found in 54 of the 1305, or 4%, of the reviewed claims. Two claims resulted in plaintiff verdicts and 16 others were settled by OMIC. Defendant ophthalmologists were awarded defense verdicts or granted motions for summary judgment by the courts four times, while 32 others were dismissed by the plaintiff without any payment by OMIC. The table below gives details on the amounts paid to settle these claims and compares  them to OMIC claims overall. Informed consent claims were more successful for plaintiffs than claims overall during the same time period, requiring a payment to resolve them in 33% versus 20% of claims. Moreover, the mean and median payment were both higher for informed consent claims. The most useful part of the claims analysis, however, is the information it provides on the two types of situations most likely to lead to miscommunication about risk.

them to OMIC claims overall. Informed consent claims were more successful for plaintiffs than claims overall during the same time period, requiring a payment to resolve them in 33% versus 20% of claims. Moreover, the mean and median payment were both higher for informed consent claims. The most useful part of the claims analysis, however, is the information it provides on the two types of situations most likely to lead to miscommunication about risk.

Vulnerable patients who accept recommended care

All patients undergoing surgery are at risk for common complications such as infection, hemorrhage, loss of vision, and damage to the eye. Patients with complex histories, or those with comorbid eye or systemic conditions, are often at higher risk. And many of these patients are elderly and non-English speaking, which can increase the obstacles to successful communication as the studies on low health literacy show. The following claims illustrate that plaintiff and defense experts alike criticized insureds for their failure to address additional risk in such patients.

An elderly patient with a history of several surgeries for a pituitary tumor and an increasing cup-to-disc ratio and pale optic nerve presented with a macular hole. The ophthalmologist recommended a vitrectomy. Postoperatively, the patient sustained significant vision loss whose cause was never determined. In his lawsuit for negligence and lack of informed consent, the plaintiff claimed the ophthalmologist assured him that his vision would improve and did not discuss any risks. Moreover, the eye surgeon asked him to sign a generic consent form that listed the type of surgery but did not specify risks either. The plaintiff expert strongly criticized the defendant ophthalmologist for not explaining how the preexisting damage to the optic nerve would exacerbate the effect of any further loss of vision. Defense experts supported the decision to perform surgery but acknowledged that if the plaintiff’s account of the discussion were to be believed, his informed consent had not been obtained. Defense counsel found the plaintiff and his wife to be sympathetic and credible, so the physician agreed with the defense attorney’s advice to settle the case for $250,000.

Another elderly, frail patient who suffered corneal decompensation after a combined cataract and glaucoma surgery testified in her deposition that the physician never told her what procedure he would be doing and never informed her that she had a cataract. She was unable to state, even at her deposition, what surgery had been performed. Plaintiff and defense experts agreed it was not clear that the patient had understood that she was consenting to a combined procedure, much less how having two done at the same time impacted the risk profile of the surgery. Her claim settled with the physician’s consent for $140,000.

A third patient who did not speak or read English did not realize that the consent form he signed was an agreement to participate in clinical research instead of for cataract surgery. When he suffered a series of complications, including capsular tear, a dislocated IOL, and a giant retinal tear, and ended up with NLP vision, he sued. The plaintiff alleged not only lack of informed consent but fraud about the clinical trial. The patient was never enrolled in research and had merely been given the wrong form. The defense was unable to get the fraud allegation and demand for punitive damages dismissed, so the physician agreed to settle the case for $200,000. The informed consent process in these claims was far from ideal. Each time, the patient accepted the information or document provided by the ophthalmologist and followed the recommendation to have surgery without asking questions or raising concerns.

Patients with strong preferences

Unlike the vulnerable patients described above, some patients are clearly engaged in the consent discussion, ask questions, and state their preferences. When those wishes seem to be ignored, they sue. One patient, for example, did not want to wear glasses after cataract surgery and affirmed this goal at each preoperative visit. She took home the procedure-specific consent form to review again. When she read that glasses were often needed after cataract surgery, she called the surgeon, changed the form to cross out that section, and mailed it back to the office. Postoperatively, she not only needed glasses but experienced pain. Efforts to ascertain the cause were in vain, but her vision improved and the pain disappeared after an IOL exchange was performed by another ophthalmologist. The plaintiff expert’s only criticism related to informed consent. Feeling his care was appropriate, the physician refused to settle. During discussions after they had rendered their verdict, members of the jury opined that the surgeon should have noted and addressed the changes to the consent form and that the plaintiff did not get the outcome she wanted. They awarded her $12,916, which covered the cost of the two procedures, and $4,200 for her pain and suffering.

Three additional lawsuits stemmed from a misunderstanding about the need for glasses after cataract or refractive surgery. Four others challenged the consent for monovision. Patients seem to better hear and remember comments that appear to promise benefits. These eight lawsuits show that ophthalmologists need to not only explain risks, but also clarify surgical goals and manage expectations. Eye surgeons should consider postponing or cancelling surgery on patients who are not willing to accept the need for glasses or the possibility of complications. This review of informed consent lawsuits shows that patients who consent to surgery may not understand what they have been told. The Hotline article will explore ways to confirm that key information has been effectively communicated.

- National Patient Safety Foundation. Health Literacy: Statistics at a Glance. http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.npsf.org/resource/collection/9220B314-9666-40DA-89DA-9F46357530F1/AskMe3_Stats_English.pdf. Accessed 11/5/14.

Please refer to OMIC's Copyright and Disclaimer regarding the contents on this website